The Aristocrat & the Able Seaman: Extract

It’s difficult to imagine a time when people didn’t know much about Titanic but it wasn’t until forty-three years after the disaster, in 1955, when Walter Lord’s book A Night to Remember was published that interest revived. In the aftermath of the sinking, in 1912, after the Press uproar died down and the Inquiries concluded, Titanic’s survivors rarely talked about what happened. They were in shock, they had what we’d call PTSD and, in 1914, just two years after Titanic sank, war broke out. The terrible number of deaths when the world’s largest liner sank – 1,496 people died – was eclipsed by the millions who died in the First World War.

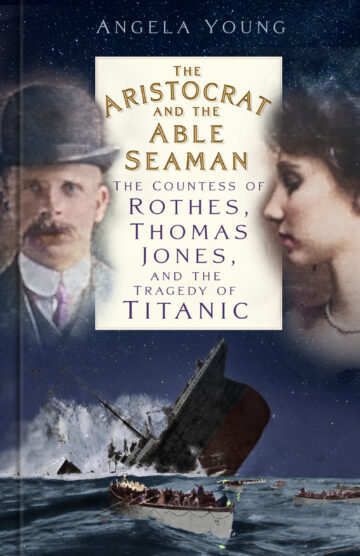

In the Introduction to the fiftieth-anniversary edition of Lord’s book, published in 2005, the American historian Nathaniel Philbrick wrote that A Night to Remember was the, ‘First significant book about Titanic for nearly forty years.’ The book was made from interviews with sixty-three survivors, including a written interview with my great-grandmother, Lucy Noël Martha Leslie, Countess of Rothes, the Aristocrat of this book. (Rothes is pronounced Roth-iz: roth rhymes with moth. Rothes is the title; Leslie is the family name.)

My own family’s interest in Titanic revived when Noël Rothes died in 1956 and her eldest son, Malcolm, and his eldest daughter, Jean Mackenzie, found a box of Noël’s Titanic papers, papers they’d never seen. There were newspaper cuttings from 1912 and a copy of Noël’s sworn statement to the British Vice-Consul at Altadena, California, made that May, a month after the disaster. There were letters from the Able Seaman of this book, Thomas William Jones, and some of Noël’s own letters; there were letters from Maria-Josefa de Satode Peñasco y Castellana (birth name, Perez de Soto y Vallejo) who survived in Lifeboat Number 8, the lifeboat that Thomas Jones commanded and Noël Rothes helped to steer. There were straightforward accounts of the disaster and emotional outpourings. I’ve quoted from Noël’s papers throughout this book and I’ve included photographs of Jones’ original letters.

Noël’s Titanic papers counteract the myths that made her remark occasionally afterwards, ‘Do remember that whatever you hear about the Titanic is not true’. Thomas Jones’ youngest daughter, Nell Jones, wrote that when the film of A Night to Remember was released in July 1958, the Press pestered her father and he became ill. He didn’t want to talk to them; he didn’t want to remember. As Dr Rudi Newman, the travel historian and author, writes, A Night to Remember is still the most historically accurate film, because of its thorough research and, ‘Because several survivors assisted with its production’, so it must have been particularly difficult for Titanic’s survivors to watch. Jones’ granddaughter Shelagh Oakes, who was only fourteen at the time, remembered her mother, Mary Ada Oakes, Jones’ eldest daughter, saying her father was very upset by the film’s publicity. Jones’ Titanic memories clearly still held the power to traumatise him forty-six years later. Mary Ada said he was, ‘Never the same’, even after the publicity died down: it brought back memories he couldn’t bear to repeat to the Press when they ‘badgered’ him.

In his book, Shadow of the Titanic, the journalist and writer Andrew Wilson wrote:

This forced forgetting – the conscious or unconscious suppression of memory – was one of the many strategies employed by those who survived. For them, the experience was like a closed book, a text that had been placed in a strongbox and locked away from both prying strangers and curious family members. It was a subject not open for analysis or discussion.

The box that Noël’s son and granddaughter found when she died was her strongbox: it held the things she didn’t want to remember, things her family hadn’t known.

In 1980, twenty-four years after Noël Rothes died, Eve Mackworth-Young, my mother, Malcolm’s second daughter, typed Noël’s handwritten material (which hasn’t been published before) and put it, and all the newspaper cuttings and other material into several albums. Many years afterwards I developed a talk about the Aristocrat and the Able Seaman from the material in my mother’s albums and quite often, after the talk, people ask if there’s a book. This is that book.

I discovered more about Twm (Tom) Titanic – as they call him where he was born, in Cemaes Bay in north Anglesey, Wales – from Shelagh Oakes and from Eric Torr, the Chairman of the Cemaes Bay History Group (pronounced Kemus). Carys Davies, Elfed Jones (no relation) of Oriel Cemaes and J Richard Williams, who live and work in Cemaes Bay, also told me about him and I read a biography at Encyclopedia Titanica. In 2012, the centenary of the sinking, I met Nell Jones when the BBC interviewed us about our ancestors.

As I researched and discovered what Noël Rothes and Thomas Jones went through on that terrifying night, I realised it was possible that many more who sailed on Titanic might have survived. Through the papers of these two courageous survivors, through evidence to the Inquiries from the Titanic Inquiry Project where complete texts of the American and British Inquiries can be read and from which the Titanic researcher Robert Ottmers has kindly given me permission to quote, and through my own research I’ve clearly seen the mistakes and miscalculations that cost the lives of 1,496 people. These things have been examined and documented by Titanic experts for a long time now but – as I frequently discover after my talk – they often fail to reach ordinary folk like me.

Noël thought there were enough lifeboats for everyone, so why weren’t there? Jones thought he was rowing his lifeboat towards the lights of a rescue ship, so why weren’t they rescued? Both heard the screams and cries of those dying in the icy waters behind them but they, and Titanic’s owners, thought the great ship, ‘Practically unsinkable’, and a, ‘Lifeboat in itself’, so why wasn’t it?

I’ve consulted Titanic experts to make sure that what you’re about to read is as accurate and myth-free as possible (any remaining errors are my own) and my intention – despite Noël’s and Jones’ silence afterwards – is to tell their Titanic stories, in some aspects for the first time, precisely because they couldn’t bear to. I want to show how their courage, kindness, resourcefulness, thoughtfulness, steadfastness and seafaring knowledge on that terrible night helped twenty-five others, and how the things they witnessed prompted my exploration of what happened (without the exaggerations) so that I can make the facts better known to people like me who aren’t Titanic experts: to give us a clearer understanding of what went wrong, why so few survived and how Maritime Law changed afterwards to make life at sea safer.

But above all, The Aristocrat and the Able Seaman is my tribute to two courageous people who – like everyone else on board the White Star Line’s magnificent new liner – never dreamt that the great ship would sink.

The Aristocrat & the Able Seaman

Publication date: 9th April 2026

The History Press | ISBN: 9781837051144 | 50 Illustrations