Seventy-five years ago, on 22 June 1948, HMT (His Majesty’s Transport) Empire Windrush arrived at Tilbury Docks, on the River Thames. She was named, as many empire ships were, for a British river, in her case the River Windrush, a small Thames tributary. Windrush brought 492 passengers to Britain from several Caribbean islands including Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago.

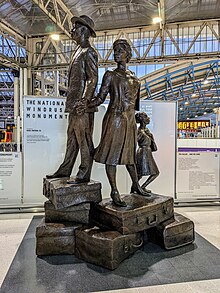

Photograph from the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI) here

The British government asked the Caribbeans to come, to help with post-second-world-war labour shortages. The hope-filled expressions and the excitement on the faces of those in the prow of Windrush breaks my heart, because we white people gave them a horrible reception. We met the Windrush Generation (those who arrived from the Caribbean between 1948 and 1971) with racism, dismissal and deprivation, instead of the jobs they were qualified for and the new beginnings: the prosperity and the equality they rightly expected from the Mother country.

And as if our white refusal to rent houses to the Caribbeans, our injustice, and our delegation of the worst jobs to them wasn’t enough, (for example, trained nurses cleaned toilets and mopped hospital floors instead of nursing) in 2012 the British government came up with the dreadful idea of making a hostile environment for immigrants without the required papers. This meant that many of the Windrush Generation, who’d arrived as children on their mother’s passports, or simply with landing cards, found themselves facing deportation back to Jamaica. Because, by then, the Home Office had destroyed thousands of landing cards and other records, so many [of the Windrush Generation] lacked the documentation to prove their right to remain in the UK.

The Windrush Scandal continues: a Windrush Compensation Scheme has been set up, but it has been criticised for low payments and slow responses to claims and, in January 2023, Suella Braverman rescinded three of the commitments to the Windrush Generation, adopted by the Home Office, after the Wendy Williams inquiry into the scandal published its report, Windrush Lessons Learned in March 2020. In that same month, the Institute for Government found that:

The British state wrongfully detained or deported 164 people, with more leaving ‘voluntarily’ following repeated pressure from the Home Office – despite having a right to stay. The true scale of who was affected is still unknown. The independent review, chaired by Wendy Williams, an inspector of constabulary, says the scandal affected “hundreds, and possibly thousands, of people” who had their ability to work denied and their access to vital benefits or treatment wrongfully removed. At its most extreme, people “were deprived of their liberty.”

It’s like saying to your relations, ‘Come live with us, work with us, make new lives with us,’ and then saying, ‘Actually, we didn’t mean with, we meant for.’ And, after decades of treating these new relations appallingly badly, saying, ‘Actually, we didn’t even mean for. We meant, we don’t want you anymore.’

Here’s a short video of London teacher, Sara Burke, leading a Windrush Scandal protest in 2018. She’s the granddaughter of Jamaican immigrants who came to Britain during the Windrush era.

There are many more video stories from Caribbean Londoners here and there are many Windrush Generation stories here.

Despite all this, Jamaican-Britons have survived and thrived and contributed magnificently, beautifully and enduringly to Britain’s arts and culture, to academic life, to political life, business and the law, to fashion and invention, religion and sports, entertainment, writing and journalism. Here’s just one list.

Below is a little about Andrea Levy, Lenny Henry and Robert & Jennifer Beckford. (I tried to find a link for Jennifer Beckford on her own, but couldn’t.) They’re all Jamaican-Britons.

In 1948 Andrea Levy’s father sailed from Jamaica to England on the Empire Windrush … her mother joined him soon after. Andrea was born in London in 1956, growing up black in what was still a very white England.

That comes from Andrea Levy’s website (sadly she died in 2019) but she was a wonderful writer who wrote poignantly-funny, thoughtfully-honest novels about the black British experience. One of them was Small Island, a novel set in 1948 and beyond, in Britain. It tells the stories of a family of black Jamaican-Britons and a family of white Britons and how welcoming (or not) the white families were to the black ones.

Image from Authors’ Lives, Andrea Levy, British Library here

Levy gave an interview to Sarah O’Reilly, an oral historian at the British Library for the library’s national archive series, Authors’ Lives in 2014. Among many recorded pieces, Levy said, in the one linked to the image above:

If you’re English, you have a sense of who you are, it comes to you … through the culture in which you live. When you’ve come from outside, or your parents have come from outside, that sense is lost and so you either take on this majority culture and say this is mine, or you have to seek out the one that has been lost to you. You have to seek it out yourself because nobody’s going to tell you the history of Jamaica in this country [Britain] … I’m still seeking it out.

In the Authors’ Lives interview O’Reilly describes Small Island:

It was inspired by Levy’s parents’ experience of moving to England and explores how migration shapes both those who travel to a new country and the people they come to live among.

It’s a wonderful novel, and also a play. I highly recommend both.

Lenny Henry (now Sir Lenny Henry) came to Britain from Jamaica on his mother’s passport, aged eight. In 1975, aged sixteen, he won New Faces and since then he hasn’t stopped working. He’s a writer, a philanthropist, one of Britain’s best-known comedians and an award-winning actor.

Between 28 April and 10 June, Henry directed and acted in his one-man show, August in England, his debut as a playwright. It’s about August Henderson, who, aged eight, comes to Britain from Jamaica with his mother, on her passport. It’s about his life, his loves, his children, his work and, tragically, about how the British government hounded him in later life and threatened to deport him, because, they claimed, he didn’t have the required documents to remain in Britain. August in England ends with filmed testimony from three Jamaican-Britons who were evicted from their homes, lost their jobs and suffered devastating and ongoing trauma as a result of the British government’s abject failure to admit they had caused the problem when they destroyed the landing cards and other records of the people they’d asked to come to Britain to help get the country back on its feet after the second world war.

Photograph by Helen Murray, from here

On his website, Henry writes, here (at the end of this link):

The only way that we can make good on all those well-meaning statements about Black Lives mattering, is if the Establishment goes out of its way to empower those black lives and all those other minorities. True diversity is diversity of colour, diversity of experience, diversity of being … . When you get all those people at the table, there will be arguments, there will be banging of the table with fists, there will be walkouts, but oh my God, the brilliance that will come out of those conversations will blow you away … . And I assure you, when we get a big win, I will do a naked streak down Pall Mall! Watch this space.

Professor Robert Beckford, Professor of Black Theology at The Queen’s Foundation, together with his wife, Jennifer Beckford, have made a four-episode programme for BBC Radio 4 called Windrush, A Family Divided. She was born in Jamaica and then came to Britain. He was born in Britain, to Jamaican parents.

Professor Robert Beckford and his Jamaican-born wife, Jennifer Beckford. On their programme they argue the pros and cons of Windrush 75 years on. Image from here

Beckford and Beckford have argued about whether the Windrush Generation benefitted from coming to Britain or not, for twenty-three years. In the first episode, Jennifer Beckford argues that, ‘Excellent people were syphoned off from the Caribbean’, and that the people who came to Britain, ‘Should have stayed at home – or gone back – to create a vibrant and economically sound Jamaica.’

In an interview, in the first episode, with an uncle and aunt, Ken and Estelle, Robert Beckford hears how Ken was helped by his employer to buy a house (he couldn’t rent because very very few white people would rent to a black person). Beckford says to Ken, ‘You faced adversity and you overcame it. Windrush is a story of overcoming and striving and being successful.’ But there are also stories of people who ignored the call from Britain, stayed in Jamaica and have been just as successful.

Both the Beckfords agree that the Windrush generation had to do the heavy-lifting in Britain, so they didn’t have to: by heavy-lifting they mean paving the way, facing the kinds of discrimination and difficulty they never faced in the Caribbean, and, in some cases, being wrongly deported from Britain back to countries they barely remember or never knew. At the end of the first episode Jennifer Beckford asks, ‘Don’t you think our children and our children’s children will fare better in the Caribbean?’

Find out how their discussions develop in subsequent programmes on Mondays in June, at 11.00am here, or on BBC iPlayer anytime, here.

The inscription by the National Windrush Monument lists the members of the Windrush Committee who commissioned the sculpture, and a poem by Laura Serrant, called You Called … We Came. The last lines of her poem are:

Remember … you called.

Remember … you called.

YOU. Called.

Remember, it was us, who came.

©Professor Laura Serrant 2017

All the people described above are radiant planets in the Jamaican-British firmament. But until the day when every single Jamaican-British person (let alone all those whose families and ancestors originally came from other countries) … until the day when every single one is seen (August in London vividly shows how it feels not to be seen), until the day when every single one feels at home in Britain, feels welcome in Britain, is free to work, live and thrive in Britain, is empowered in Britain without any kind of hindrance or racist restriction or microaggression, white people must never stop working to make all British systems, the establishment, particularly, and every white person individually, antiracist.

And a PS: it’s looking more and more likely that Jamaica will decide to become a republic, perhaps as early as 2024. To paraphrase Lenny Henry, watch their space.

Leave a Reply