Black History Month’s theme in the UK is Standing Firm in Power and Pride

Paulette Hamilton, Labour MP for Birmingham Erdington writes:

This year’s theme … is deeply personal to me, not just as Birmingham’s first Black MP, but as a woman who has dedicated her life to fighting for health equity in our communities. I’ve always said my journey into politics was forged in the NHS, where I worked as a district nurse for 25 years. Day after day, I saw the disparities in our health system, the barriers to access, the gaps in outcomes, and the quiet neglect that our communities endured. That experience didn’t just shape my career, it ignited a fire in me to challenge systemic inequity head-on. …

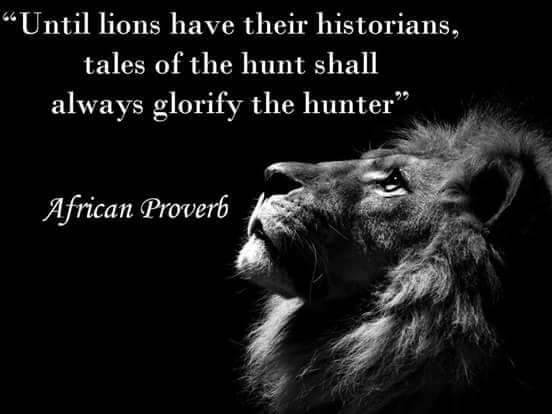

More than 30 years of fighting for health equity has taught me that our power lies in our pride, and our pride lies in our refusal to accept injustice. Whether in politics, our health system, or our daily lives, we must strive for leadership in all spaces, we must lead with conviction, because “A man who stands for nothing will fall for anything Malcolm X [my bold]”.

Kerry James Marshall, the Black artist whose retrospective is at the Royal Academy in London until early 2026, is clear where he proudly stands. In his recent interview with John Wilson for This Cultural Life he said:

If you can match the sophistication, the skill and the complexity of the works that are already in there [an exhibition / museum] then you will be in there too.

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Porch Deck), 2014 : permission to reproduce requested of David Zwirner, 6x

And the late Noah Davis, whose retrospective was at the Barbican last spring, stands proudly when he talks about his work:

I wanted to make somethlng normal. I wanted to make Black people normal. That was my whole thing. We are normal, right?

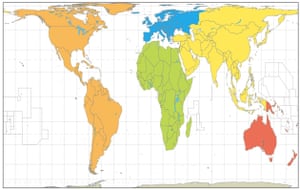

Of course Black people are normal. But white people like me have been intensely and immensely slow, as a race and individually, to recognise and acknowledge that normality: to recognise the humanity in every single one of our Black and Brown and Yellow fellows; intensely and immensely slow to stand proudly beside them.

In this poignant work called Painting for My Dad, Davis gives his dead father a lamp to light his way as he stands at the edge of the universe.

Painting for My Dad, 2011 : permission to reproduce requested of David Zwirner, 6x

We must each keep a lamp firmly lit to show us where we stand.